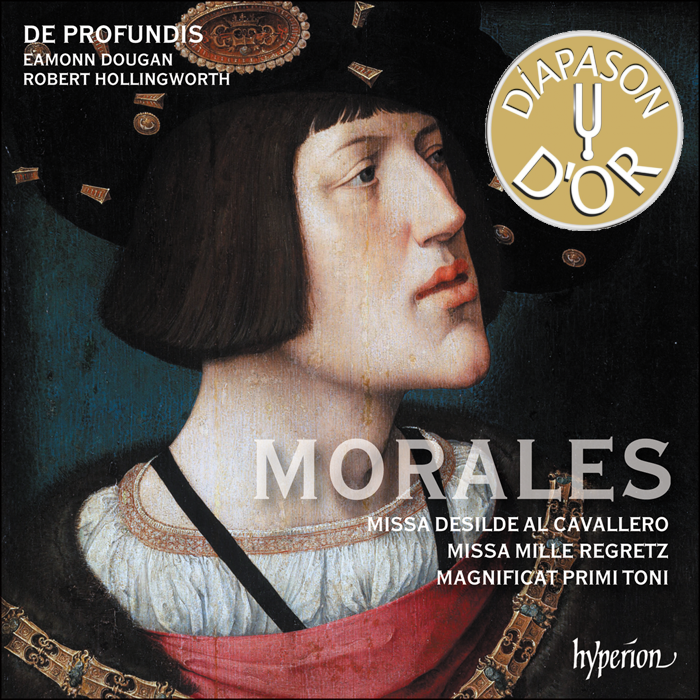

This album, the first of a planned series of twelve intended to record all of Morales’s Masses and Magnificats, begins with the Missa Mille regretz, in six voices. It is his best-known Mass today, probably because it is based on a famous song attributed (rightly or wrongly—there is some debate) to none other than Josquin des Prez.

2023

Eamonn Dougan

Robert Hollingworth

Chanson: Mille regretz (Josquin)

Missa Mille regretz (1535 & 1544 versions)

Magnificat primi toni

Song: Desilde al cavallero (anon)

Missa Desilde al cavallero

The choir chisels this luxurious polyphony with the care of a relief sculptor, the twenty English singers turning the phrases with understanding and shape. Their sonorous flourishing far surpasses that of [previous recordings]. The adventure begins – and in the most auspicious way!

Díapason

Programme notes

The Mass was a relatively early work, copied into a Vatican manuscript between 1535 and 1537 (i.e. in his first couple of years there), and was surely written in honour of, and possibly as a gift for, Emperor Charles V, who is known to have loved the song: indeed, when Morales published it in his Missarum liber primus of 1544, he was careful to put Charles’s arms in the initial to the Kyrie.

Curiously, the 1544 print replaced the whole Sanctus, and Agnus I & III as copied in the earlier Vatican manuscript. This has to be a revision by Morales himself, though the originals (here presented separately) are perfectly satisfactory pieces of music. Several of the old sections feature a superius whose note values are lengthened via a canon, for the effect of the Mille regretz tune floating gently over the top of the texture as the other voices chug below—a favourite technique of Peñalosa’s, and one wonders whether it seemed fresh to Morales in post-Seville years but fell out of fashion by the 1540s. Certainly the 1544 Mass (with its recomposed movements) is more of a unified work of art; but listen to the Osanna of the earlier version of the Sanctus if you want to hear what ‘Hosanna in the highest’ is all about.

The Missa Mille regretz has been classified as a cantus firmus Mass, for it preserves in its own superius part the top voice of the song, quite strictly presented, over and over; but the remaining voices contain so many references to the tune, and to the other voices of the song, and sometimes to recognizable chunks of the song’s harmony, that it has strong elements of the parody Mass as well. Indeed, Morales’s level of invention in keeping the song going in one part while quoting it in the others is quite dazzling. Especially gorgeous are the ‘Et incarnatus’, which combines various phrases and voices of the song into a swirling vision of Mille regretz, and the clear echo of Kyrie I at the opening of the later (1544) version of Agnus Dei I.

In his own time, and for a long time thereafter, Morales was best known throughout the Catholic world for his Magnificats—a set of eight, one for each of the church modes, each setting all twelve verses of the canticle, as it was sung in the papal chapel. Five of them were published in that way in 1542, but when it came time to print all eight in 1545, Morales split them into odd and even verses, evidently to attract buyers who sang the Magnificat in the usual alternatim style. Thus they were much copied and re-printed for many years and sung all over Europe and in the New World.

Here we have the first of the set, the Magnificat primi toni—that is on church mode I, or Dorian, in this case notated on G with a flat—restored to its Vatican completeness, as it was included in the initial 1542 print. Like all his Roman Magnificats, it is normally in four voices, though verses 5 and 7 are in three, and verse 12 expands to six, including an altus part derived canonically from one of the cantus voices for a spectacular finish. The Magnificat tone can always be heard distinctly somewhere in the four- and six-voice verses.

The Missa Desilde al cavallero is much less familiar today, and apparently in its own time too: it survives in only one copy, a manuscript in Milan that otherwise contains Masses by Josquin and La Rue, suggesting that this too is an early work, possibly written before Morales arrived in Rome. It is based on a popular Spanish song that we know today from an intabulation by Diego Pisador (as performed here), a variation set by Antonio de Cabezón, and a complex and refined polyphonic quintet by Nicolas Gombert.

Here again Morales thwarts our modern system for classifying Renaissance Masses. The tune appears in the tenor, which moves somewhat slower than the other three voices, at the beginning of each movement, always coming in last (but imitated in the other voices), all of which hints at a tenor cantus firmus Mass in the good old—by now antique—style; but he never presents it the same way twice, and often gives it up part way through a movement. The Osanna is a 5-ex-4 canon and the Benedictus a 4-ex-3.

These two Masses and the Magnificat, then, seem to have been written relatively early in Morales’s career. All three are based on music which his singers, and his audience, would have known well, and in each case their models are presented very prominently. It is a situation that threatens boredom—a threat on which he never delivers. This music shows Cristóbal de Morales as the master of invention and variety even as a young man.

Author Bio

Kenneth Kreitner, Benjamin W. Rawlins Professor of Musicology, received his PhD in musicology from Duke University in 1990 and joined the faculty at Memphis State that fall. A scholar of Spanish Renaissance music, historical performance, and nineteenth-century American amateur bands, he is the author of Robert Ward: A Bio-Bibliography (Greenwood Press, 1989), Discoursing Sweet Music: Town Bands and Community Life in Turn-of-the-Century Pennsylvania (University of Illinois Press, 1990), and The Church Music of Fifteenth-Century Spain (Boydell Press, 2004). He has also published articles in Early Music, Early Music History, Musica Disciplina, the Revista de Musicología, and the Journal of the Royal Musical Association. Dr. Kreitner is an active performer on early brass and woodwind instruments and directs the University’s Collegium Musicum. He received the University of Memphis Alumni Distinguished Teaching Award in 2000; the Robert M. Stevenson Award, for outstanding scholarship in Iberian music, from the American Musicological Society in 2007; and the Christopher Monk Award, for life-long contributions to study and/or performance in the field of brass history, in 2012.