Description

2016

David Skinner

Rex autem David

Gloriosae virginis Mariae

Beata mater

Dimitte me ergo

Non vos relinquam orphanos/Magnificat primus tonus

O rex gloriae/Magnificat secundus tonus

Virgo prudentissima

Conserva me, Domine

Assumpsit Jesus Petrum

In ferventis/Magnificat quartus tonus II

Hodie completi sunt dies Pentecostes

Among the many musical treasures that survive in the archives of Toledo Cathedral there is a great choirbook devoted entirely to works by ‘Bernardinus Ribera’. It is known to musicology as E-Tc6. Let’s call it the Ribera Codex. It was the work of Toledo’s renowned copyist Martin Pérez, and decorated with illuminations by Buitrago. Beautiful to behold, it is massive; bound in metal-studded, leather-covered wooden boards, the one hundred and fifty-nine parchment folios are resplendent in their fine musical notation with exquisite headings and decorated initials. Or so they should have been if we still had this volume as it was in 1570, copied in the final year of Ribera’s tenure as maestro de capilla. Many years later some vandal sliced out whole folios, presumably the most beautifully decorated, and he cut out many of the elaborate initials of the texts, thus creating holes which have swallowed the notation on the reverse. This vandalism probably happened in the eighteenth century. Little other damage or deterioration is to be seen. Its mutilated survival still constitutes the only source of the majority of the known compositions of this obscure maestro.

So much is missing from many of the compositions that they are beyond recovery. There were two full Lady Masses—Missae de beata virgine—one for four voices, the other for five. Both included the medieval tropes (Spiritus et alme … etc.), and polytextual passages such as the words and music of Ave Maria gratia plena being sung in several sections of the five-part Credo. It’s a shame that these Masses are not fully retrievable; twelve folios were torn from this part of the manuscript, and there are numerous vandal-holes in the pages that remain. With the motets we are more fortunate.

Although twenty-five folios (forty-eight pages of music) were torn out, we can confidently present six of the nine motets in the Ribera Codex with just a few small lacunae ‘repaired’. One missing page was recently found elsewhere, sliced in two; it restored the beginning of Regina caeli. We have lost most of an eight-voiced Ascendens Christus. Also irreparable is O quam speciosa festivitas, a special Toledo motet for St Eugenius (for six voices). An imposing Gloriosae virginis Mariae for eight voices lacks its beginning, but we have presented it with the first three words in plainsong and our editorial restoration of some missing voices in the first fourteen bars of polyphony.

The Codex ends with what should have been eight Magnificats, the first half of a set of sixteen, two (odd-verse and even-verse) to each of the eight Tones, polyphony alternating with the chanted recitation formulae. The Codex contains four of these pairs, setting Tones 1–4. We do not know if Ribera composed Magnificats to Tones 5–8. Sadly, only three of the existing set can be transcribed complete with minimal editorial patching. These are recorded here, each preceded and followed by appropriate plainsong antiphons.

It may seem like a lot of bad news that so much is missing or damaged. The good news is that we have another source for five of Ribera’s motets; two of them, Virgo prudentissima and Rex autem David, are in the Toledo Codex, but there are three that are not: Dimitte me ergo, Assumpsit Jesus Petrum and the magnificent seven-voiced Vox in Rama. The latter, weeping for the loss of children, has twenty-six repeated cries of ‘Rachel’ (accented short–long in the Spanish manner). It is the piece that first got the present writer interested in Ribera, many years ago.

This set of part-books is now kept at the Real Colegio de Corpus Christi in Valencia. The books were donated to the college in 1641. They were copied some forty years earlier. The five Ribera motets are in mixed company, if fame is the criterion. Nearly eighty works demonstrate the compiler’s broad and excellent taste. ‘Lasso’, Palestrina, Ruffo and Vecchi represent Italy; from Spain there is, above all, Guerrero (of Seville), and also a veritable host of lesser masters, all from the east-coast provinces, Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia and Murcia: Comes, Cotes, Company, Pérez, Pujol, Robledo and Josep Gay, to name a few.

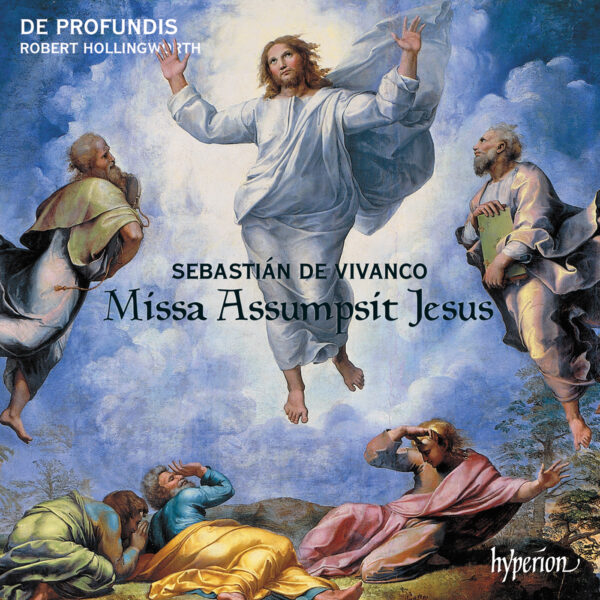

Ribera was very much a man of Spain’s south-east. He was born in Játiva (Valencia) probably in 1520. His father, Pedro, was then maestro de capilla of the collegiate church there. Soon the family moved to Orihuela (Alicante), thence later to Murcia: Pedro was certainly maestro at the cathedral in 1535. Bernardino must have received his training there. His first known major appointment was to the cathedral at Ávila where he succeeded the maestro Espinar (died 1558). He took up the post in June 1559. There he was the mentor not only of the young Tomás Luis de Victoria but also of Sebastián de Vivanco. Ribera left the Ávila post at the end of 1562 and became maestro de capilla at Toledo early in 1563. He stayed until 1570, succeeded by Andrés Torrentes. It has been assumed in modern dictionaries that Ribera had died, but recent research has shown that he in fact returned to his roots and became maestro at Murcia Cathedral from 1572 until 1580.

What are we to make of Ribera’s works, of his position in the hierarchy of Hispanic composers, and of his possible influence on Victoria? There is not enough of his music, nor enough variety in it, to award Ribera a place among the great masters, Morales, Guerrero and Victoria. His style seems influenced by Morales and by the mid-century musicians from the Low Countries brought in by Charles V and Philip II for their Capilla Flamenca. Ribera’s general manner is reminiscent of Gombert and his generation. It is very linear, very horizontal. Luxuriant tendrils of vocal lines take precedence over vertical harmonic (dare one say Palestrinian?) balance. But there are passages with clear melodic triads in the approaches to final cadences. Ribera is a link between the era of the Josquin emulators and that of Guerrero, Spain’s most popular composer in the late 1500s. He must have had some influence upon the teenage Victoria, but it is difficult to detect in Victoria’s very Roman style.

Ribera surprises us with his startling passage in Rex autem David when the King laments ‘Absalon, fili mi’, sung eleven times by the five voices in imitation, descending mournfully by semitones. This chromaticism was suppressed in Toledo’s Ribera Codex where the sharps are erased, but they mostly survive in the Valencia part-books, enabling our restoration. In other motets Ribera uses frequent intermediate cadences at phrase-ends, interlocking so that sharps in one voice are very close to flats or naturals in others, sometimes colliding. This is a kind of astringent seasoning of the polyphonic mix, not a means of expressing particular words. He surprises again when he sets the desolate text of Dimitte me ergo in a major mode and achieves mournful pathos. The Psalm Conserva me, Domine has a sturdy grandeur worthy of Gombert or even Tallis. The tenderness of Beata mater has some overlapping phrases of haunting beauty. But Ribera anticipates Vivanco (also a young pupil at Ávila) when he ends his Magnificats with multi-voiced doxology verses containing strict canons.

This recording presents Ribera’s surviving works that are complete or easily restored. This music offers a rewarding experience to singers, with its rich polyphony and its intricate weaving of inner voices. It is not all darkly penitential, but Ribera certainly was expert at that.

Bruno Turner

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.