Description

2023

Eamonn Dougan

Robert Hollingworth

Chanson: Mille regretz (Josquin)

Missa Mille regretz (1535 & 1544 versions)

Magnificat primi toni

Song: Desilde al cavallero (anon)

Missa Desilde al cavallero

Cristóbal de Morales may have been the most famous composer of sacred music in all western Europe in the period between the death of Josquin in 1521 and the rise of Palestrina and Lassus in the 1550s. But at the same time, he remains a mysterious and tragic figure in the history of Renaissance music.

Morales was born in Seville around 1500 or a little before, and if he was educated in the cathedral school there, as seems most likely, he certainly had talented teachers: Pedro de Escobar was master of the choirboys at Seville from 1507 to 1513/14, and Francisco de Peñalosa, who was officially employed by the royal chapel, spent a good deal of his time in Seville and considered the city his home. In 1535, after chapelmaster jobs in Ávila and Plasencia, Morales joined the papal choir in Rome, and during the ten years he spent either there or on travels with the Pope’s retinue he found lasting international success, appearing in printed anthologies (but with his name prominent in their titles) as early as 1540, and publishing two large books of Masses under his own name in 1544. But by the time he left Rome to become chapelmaster at Toledo Cathedral in 1545, something had gone very wrong.

Morales’s absences seem to have begun early in his time at the Vatican, and, as the years went on, they became more frequent and longer, and were more carefully specified as being the result of illness. The exact nature of his ailment is never explained; recurrent malaria has been suggested, as well as rheumatoid arthritis, and here in the twenty-first century it is easy to wonder about, say, bipolar disorder. For whatever its effects on Morales’s life as a singer, the illness did not seem to slow down his productivity as a composer. Even in the Toledo period, when he was plagued with further illness, serious financial problems, musical dissatisfactions and difficulties in managing the choirboys under his care, he remained at the top of his artistic game, as revealed in the glorious service music recently recovered by Michael Noone from the water-damaged manuscript Toledo 25.

In any case, Morales lasted less than two years in Toledo before resigning in August 1547 and moving on to lowlier employment—and continued illness and unhappiness—in Marchena and Málaga. In the summer of 1552 the chapelmastership at Toledo came open again; Morales applied and, in a move that suggests that he was not remembered warmly, was required to compete for the position with the other candidates. But before the competition could be held, he died, somewhere in his early fifties.

It’s a sad story of frustration, disappointment and misery, told in short prosaic documents that individually conceal much but accumulate their melancholy weight as Morales’s life goes on. And it is a story made all the more poignant by the beauty of the music he has left behind which, at its best—and it is often at its best—combines the elegance and the imitative virtuosity of the so-called post-Josquin generation (the ‘perfected style’ in Richard Taruskin’s perceptive words) with a clarity and a human intensity not often seen in his Northern contemporaries.

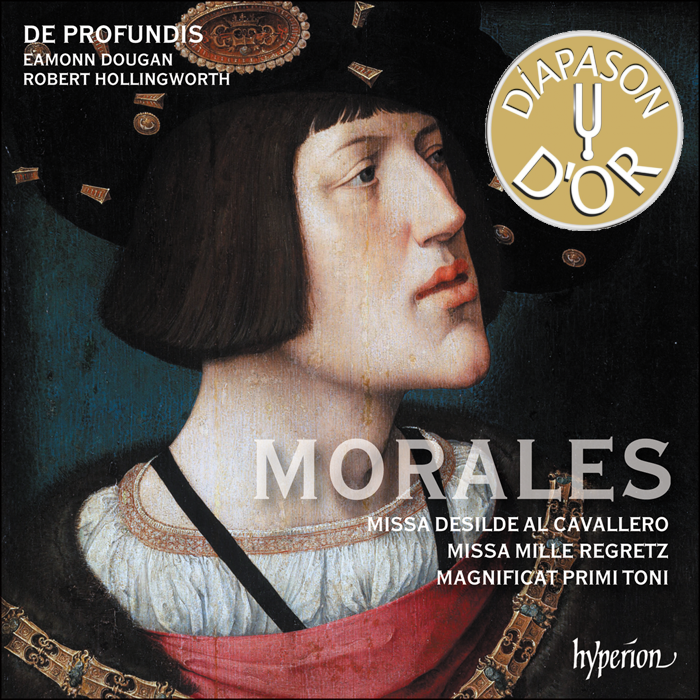

This album, the first of a planned series of twelve intended to record all of Morales’s Masses and Magnificats, begins with the Missa Mille regretz, in six voices. It is his best-known Mass today, probably because it is based on a famous song attributed (rightly or wrongly—there is some debate) to none other than Josquin des Prez. The Mass was a relatively early work, copied into a Vatican manuscript between 1535 and 1537 (i.e. in his first couple of years there), and was surely written in honour of, and possibly as a gift for, Emperor Charles V, who is known to have loved the song: indeed, when Morales published it in his Missarum liber primus of 1544, he was careful to put Charles’s arms in the initial to the Kyrie.

Curiously, the 1544 print replaced the whole Sanctus, and Agnus I & III as copied in the earlier Vatican manuscript. This has to be a revision by Morales himself, though the originals (here presented separately) are perfectly satisfactory pieces of music. Several of the old sections feature a superius whose note values are lengthened via a canon, for the effect of the Mille regretz tune floating gently over the top of the texture as the other voices chug below—a favourite technique of Peñalosa’s, and one wonders whether it seemed fresh to Morales in post-Seville years but fell out of fashion by the 1540s. Certainly the 1544 Mass (with its recomposed movements) is more of a unified work of art; but listen to the Osanna of the earlier version of the Sanctus if you want to hear what ‘Hosanna in the highest’ is all about.

The Missa Mille regretz has been classified as a cantus firmus Mass, for it preserves in its own superius part the top voice of the song, quite strictly presented, over and over; but the remaining voices contain so many references to the tune, and to the other voices of the song, and sometimes to recognizable chunks of the song’s harmony, that it has strong elements of the parody Mass as well. Indeed, Morales’s level of invention in keeping the song going in one part while quoting it in the others is quite dazzling. Especially gorgeous are the ‘Et incarnatus’, which combines various phrases and voices of the song into a swirling vision of Mille regretz, and the clear echo of Kyrie I at the opening of the later (1544) version of Agnus Dei I.

In his own time, and for a long time thereafter, Morales was best known throughout the Catholic world for his Magnificats—a set of eight, one for each of the church modes, each setting all twelve verses of the canticle, as it was sung in the papal chapel. Five of them were published in that way in 1542, but when it came time to print all eight in 1545, Morales split them into odd and even verses, evidently to attract buyers who sang the Magnificat in the usual alternatim style. Thus they were much copied and re-printed for many years and sung all over Europe and in the New World.

Here we have the first of the set, the Magnificat primi toni—that is on church mode I, or Dorian, in this case notated on G with a flat—restored to its Vatican completeness, as it was included in the initial 1542 print. Like all his Roman Magnificats, it is normally in four voices, though verses 5 and 7 are in three, and verse 12 expands to six, including an altus part derived canonically from one of the cantus voices for a spectacular finish. The Magnificat tone can always be heard distinctly somewhere in the four- and six-voice verses.

The Missa Desilde al cavallero is much less familiar today, and apparently in its own time too: it survives in only one copy, a manuscript in Milan that otherwise contains Masses by Josquin and La Rue, suggesting that this too is an early work, possibly written before Morales arrived in Rome. It is based on a popular Spanish song that we know today from an intabulation by Diego Pisador (as performed here), a variation set by Antonio de Cabezón, and a complex and refined polyphonic quintet by Nicolas Gombert.

Here again Morales thwarts our modern system for classifying Renaissance Masses. The tune appears in the tenor, which moves somewhat slower than the other three voices, at the beginning of each movement, always coming in last (but imitated in the other voices), all of which hints at a tenor cantus firmus Mass in the good old—by now antique—style; but he never presents it the same way twice, and often gives it up part way through a movement. The Osanna is a 5-ex-4 canon and the Benedictus a 4-ex-3.

These two Masses and the Magnificat, then, seem to have been written relatively early in Morales’s career. All three are based on music which his singers, and his audience, would have known well, and in each case their models are presented very prominently. It is a situation that threatens boredom—a threat on which he never delivers. This music shows Cristóbal de Morales as the master of invention and variety even as a young man.

Kenneth Kreitner

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.